ภาพประกอบ Johannes Plenio / Pexels

The world is not ready for the long grind to come บทความของ Rushir Sharma ใน Financial Times พูดถึงภาวะเศรษฐกิจยุคหลังโรคระบาด (post-pandemic) ว่าจะมีสภาพ “ยืดเยื้อยาวนาน” (The Long Grind) ซึ่งโลกยุคหลังๆ ไม่เคยเจอแบบนี้มาก่อน

Sharma บอกว่าการจัดการเศรษฐกิจของรัฐบาลและธนาคารกลางในยุคหลังๆ ทำได้ดีขึ้นมาก (เทียบกับยุคก่อนหน้า) ทำให้โลกเจอภาวะเศรษฐกิจถดถอยน้อยลงมาก

Over the past half century, as governments and central banks teamed up ever more closely to manage economic growth, recessions became fewer and farther between. Often they were shorter and shallower than they might have been.

Since 1980, the US economy has spent only 10 per cent of the time in a recession, compared with nearly 20 per cent between the end of the second world war in 1945 and 1980, and more than 40 per cent between 1870 and 1945.

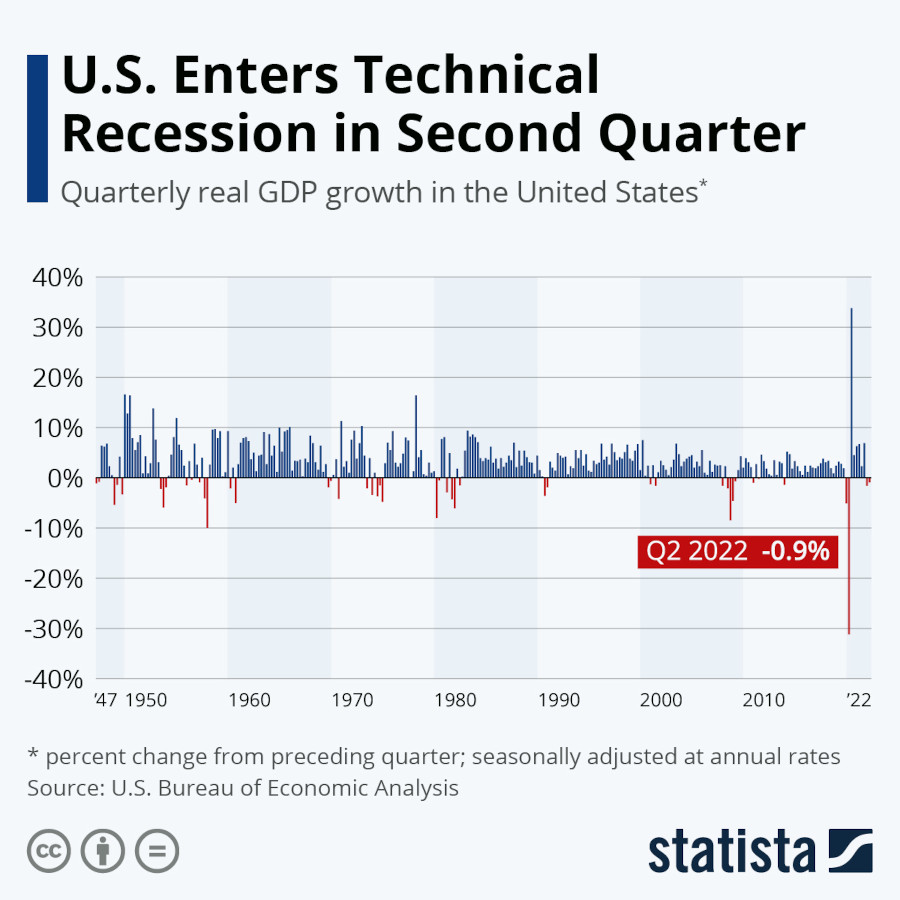

อ่านแล้วสนใจอยากดูตัวเลข เลยลองหากราฟ GDP ย้อนหลังของสหรัฐมาดู เจอของ Statista เป็นรายไตรมาสเลย ก็ทำมาเห็นภาพดี

ที่มา – Statista

รัฐบาลและธนาคารกลางของชาติใหญ่ๆ ใช้มาตรการกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจ เพิ่มเงินลงทุนภาครัฐ หรือซื้อสินทรัพย์เพื่อพยุงราคา งบประมาณส่วนนี้เพิ่มขึ้นมาก (เทียบสัดส่วนต่อ GDP) ในรอบหลายปีให้หลัง

One increasingly important reason is government rescues. Combined stimulus in the US, the EU, Japan and the UK, including government spending and central bank asset purchases, rose from 1 per cent of gross domestic product in the recessions of 1980 and 1990 to 3 per cent in 2001, 12 per cent in 2008 and a staggering 35 per cent in 2020.

ผลคือช่วงทศวรรษ 1980-2020 ระยะเวลาประมาณ 40 ปี เศรษฐกิจโลก “ค่อนข้าง” เสถียร แม้มีวิกฤตอยู่บ้างเช่น ต้มยำกุ้งปี 1997 หรือ Financial Crisis ปี 2007-2008 แต่ผลกระทบก็ถือว่าน้อยเมื่อเทียบกับวิกฤตยุคก่อนๆ

อย่างไรก็ตาม สถานการณ์ปี 2020 ที่เกิดปัญหา COVID ทำให้ภาพรวมของเศรษฐกิจแตกต่างไปจาก 4 ทศวรรษที่ผ่านมา

- การล็อคดาวน์ทำให้เศรษฐกิจโลกสะดุดมาก (ดูกราฟประกอบ)

- แต่แพ็กเกจช่วยเหลือของรัฐบาลทั่วโลกนั้นออกมาเร็วและแรงมาก (โดยเฉพาะของสหรัฐ) จนทำให้คนบางกลุ่ม (เช่น แรงงานออฟฟิศ white-collar) แทบไม่รู้สึกเลยว่ามีวิกฤต แค่ถูกล็อคดาวน์อยู่บ้าน ชีวิตไม่สะดวกกว่าเดิมเท่านั้น

- ผลกระทบทางเศรษฐกิจในทางลบต่อคนกลุ่มนี้จึงน้อย (เคสของประเทศไทยที่พึ่งพาท่องเที่ยวสูงก็จะอีกแบบ) และกลับทำให้สินทรัพย์กลับเพิ่มขึ้นจากมาตรการกระตุ้นต่างๆ ปี 2021 เราจึงเห็นตลาดหุ้นขึ้น ราคาคริปโตขึ้น ราคาบ้านขึ้นมากมาย

Government bailouts in the pandemic came so fast and large that it felt to many people, particularly white-collar employees working from home, as if the recession never happened. Their incomes and credit scores went up. Their wealth exploded with rising stock and bond markets. Now this experience of recession as a non-event seems baked into the professional psyche.

In 2020, governments injected so much money into the economy that consumers are still sitting on much of it two years on — $1.5tn in the US alone.

อย่างไรก็ตาม หลังมาตรการกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจ (ที่มามองย้อนหลังตอนนี้) อาจใหญ่เกินความจำเป็น (แต่ตอนนั้นไม่มีใครรู้ว่าวิกฤตมันจะหนักเบาแค่ไหน) สิ่งที่เกิดตามมาคือภาวะเงินเฟ้อ ที่เกิดจากปัจจัยหลัก 2 อย่างคือ 1) ซัพพลายเชนสินค้ามีปัญหาช่วง COVID และ 2) revenge spending ผู้บริโภคซื้อสินค้า-บริการระบายแค้น

หลังปัญหาซัพพลายเชนและ revenge spending เริ่มคลายตัวตามธรรมชาติ เงินเฟ้อเริ่มลดระดับลงมา แต่ก็ยังสูงกว่าช่วงก่อน COVID

The key sticking point is inflation. This is now retreating almost as quickly as it surged last year — as supply chains normalise and “revenge spending”, unleashed by the end of lockdowns and boosted by stimulus, calms down. But it is not likely to return to its pre-pandemic level of under 2 per cent.

เหตุผลที่เงินเฟ้อ (ในภาพรวม) ไม่ลดลง มีหลายอย่างคือ

ค่าแรงแพงขึ้น คนยอมทำงานน้อยลง กระแส great resignation (แห่ลาออกจากนายจ้างที่ไม่ดี), quiet quitting (เช้าชามเย็นชาม) กลายเป็นเรื่องปกติที่พบเจอได้ทั่วไป

One in eight people say they plan “no return” to pre-pandemic activities, including work. The number of hours people of all ages want to work plunged, and their attitude has changed as well. Social media celebrates “quiet quitting” and “acting your wage” — meaning do what you are paid for, and no more.

บวกกับเทรนด์ระยะยาว คนเกิดน้อยลง ที่เป็นปัญหาอยู่ก่อนแล้ว พอยิ่งมีโรคระบาด คนยิ่งไม่อยากมีลูกเข้าไปอีก ประชากรวัยทำงานจะยิ่งลดลงในระยะยาว

birth rates have been falling for years but are now rapidly shrinking working-age populations.

และเทรนด์ระยะยาวอีกอันคือ Deglobalization ภาพรวมการค้าการลงทุนของโลกจะลดลง การย้ายฐานผลิตไปยังเอเชียจะน้อยลง เปลี่ยนมาใช้ประเทศใกล้ๆ (ในบริบทของสหรัฐคือเม็กซิโก) เป็นฐานผลิตสินค้าแทน

Countries are retreating inward, offshoring to the nearest and most friendly nations rather than to the least costly.

ปัจจัยเหล่านี้จะทำให้เกิด “ระดับเงินเฟ้อ New Normal” (ดอกเบี้ยนโยบายเพิ่มจาก 2% เป็น 4%) กลายเป็นมาตรฐานใหม่ของโลกหลัง Covid ซึ่งจะทำให้รัฐบาลและธนาคารกลางมีเครื่องมือกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจน้อยลง (บทความเก่าที่เคยเขียน The Age of Tight Money)

The pressure from demographics and deglobalisation will push the new normal for inflation higher, closer to 4 than to 2 per cent.

This will make it harder for central banks to cut rates to counter the next recession. Higher rates mean governments can borrow and spend heavily to stimulate sluggish economies only at risk of inviting punishment in the global bond markets

หากโลกเราเกิดภาวะเศรษฐกิจถดถอยรอบหน้าอีก มันจะเข้าสู่พรมแดนใหม่ที่ไม่เคยเจอกันมาก่อน (อย่างน้อยก็ในหลายสิบปีมานี้) ภาวะถดถอยจะยืดเยื้อยาวนานยิ่งกว่า ตามที่ Sharma เรียกมันว่า The Long Grind นั่นเอง

While the next downturn may take longer to hit, it is likely to take an unfamiliar shape, possibly not much deeper but more enduring, as stickier inflation forces central banks and government rescue teams to the sidelines. The world is not ready for the long grind ahead.