ฟัง Hideo Kojima จัดรายการ podcast ใน Spotify เล่าเรื่องที่มาของ Metal Gear ก็สนุกดี

- Kojima เข้าสู่วงการเกมในช่วงครึ่งหลังของทศวรรษ 80s เกมยุคนั้นนิยมเกมแนวแอคชั่น ยิงปืนใส่ศัตรู แต่ไม่มีเนื้อเรื่อง เรารู้ว่าตัวละครเราเก่ง ยิงปืนชนะศัตรู แต่ไม่รู้ว่าตัวละครทำสงครามไปทำไม เรื่องไม่มีที่มาที่ไป เลยเป็นปมในใจของ Kojima ที่อยากทำเกมที่เล่าเนื้อเรื่องด้วย

- ในอีกด้าน เครื่องเกม MSX ที่นิยมในญี่ปุ่นยุคนั้น มีสมรรถนะไม่พอในการแสดงกระสุนปืนจำนวนมากๆ ในฉากได้ เลยเป็นข้อจำกัดทางเทคนิค ที่เขาพยายามแก้โดยการออกแบบเกมที่ตัวเอกไม่ต้องมีอาวุธ และใช้วิธีหลบหลีกศัตรูเอาแทน จึงกลายมาเป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของเกมแนว stealth

- ในยุคแรกๆ ผู้คนไม่เข้าใจว่า Kojima จะทำอะไร ตอนนั้นเขาเป็นพนักงานหน้าใหม่ใน Konami เลยไม่มีใครสนใจมาทำโปรเจคนี้ แต่พอดันโครงการไปสักพัก เริ่มมีสิ่งของที่จับต้องได้ คนก็เข้าใจเขากันมากขึ้น เหตุการณ์แบบเดียวกันเกิดกับอีกเกมของเขาคือ Boktai: The Sun Is in Your Hand ที่ลง GBA ปี 2003 เล่นเกมโดยใช้พลังแสงอาทิตย์ วัดจากเซ็นเซอร์ที่ฝังในตลับเกม คนก็ไม่เข้าใจเหมือนกัน (ล้ำเกินสินะ)

- เขาทำเกมแนว stealth อยู่นานกว่าจะติดตลาด จนถึง Metal Gear Solid 3 โน่น บริษัทอื่นๆ ถึงหันมาทำเกมแนว stealth กันบ้าง และค่อยยกย่องว่า Kojima เป็นผู้ให้กำเนิดเกมแนวนี้

- มีคำถามว่าทำไม Metal Gear ถึงได้รับความนิยม Kojima บอกว่าไม่รู้เหมือนกัน (555) แต่แฟนเกมมักมาคุยกับเขาว่าเป็นเพราะเนื้อเรื่องของเกมที่ละเอียดสมจริง ตัวละครมีความลึก มีเรื่องราว (บอสทุกตัวมีเรื่องราว) ไม่ได้เป็นเพราะตัวเกมเพลย์

- ที่มาของชื่อ Solid Snake มาจากคำว่า Snake คืองู ที่เลื้อยแบบไม่มีเสียง ไม่ค่อยมีใครมองเห็น เหมาะสำหรับเกมแนว stealth (เขายังยกตัวอย่าง “Fox” หมาจิ้งจอกที่ย่องมาแบบเงียบๆ ซึ่งนำไปใช้ในหน่วย Foxhound ในเกม) แล้วเติมคำว่า Solid ที่ความหมายขัดแย้งกันเข้ามาข้างหน้าชื่อให้ดูคอนทราสต์

- Solid Snake ยุคแรกๆ MSX ไม่มีใบหน้า พูดไม่ได้เพราะข้อจำกัดทางเทคนิคของฮาร์ดแวร์ยุคนั้น พอมาถึงยุค PlayStation ที่ฮาร์ดแวร์ใส่หน้า ใส่เสียงพูดเข้ามาได้แล้ว พอ Snake พูดมากๆ ก็ทำให้แฟนเกมญี่ปุ่นยุคเก่าไม่พอใจ เพราะผิดอิมเมจ (555)

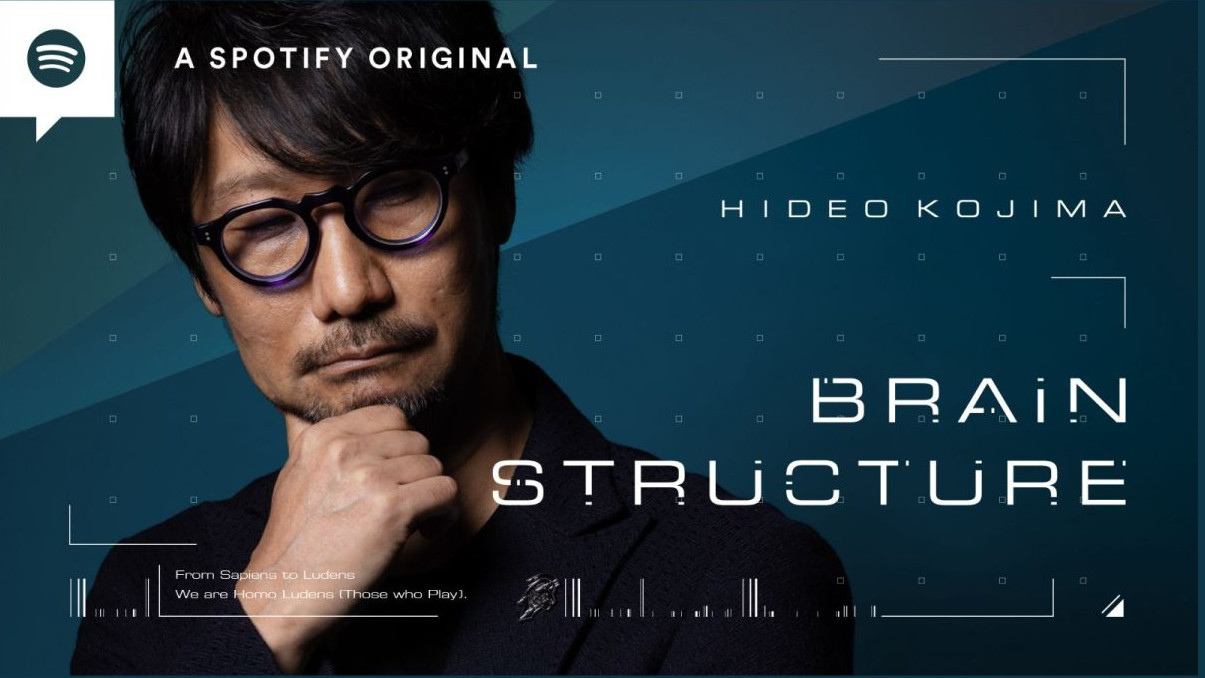

เพิ่มเติม บทสัมภาษณ์ Kojima ใน Spotify เนื่องในโอกาสทำ podcast เล่าเรื่องวิธีการทำงานของ Kojima

วิธีการทำงานสร้างสรรค์ (creative process) ของ Kojima คือทำทุกอย่างพร้อมกัน ไม่แยกส่วน แล้วกลับมาแก้เรื่อยๆ (refinement) ทุกวันให้เข้ารูปเข้ารอย ซึ่งเขาบอกว่า Pixar ก็ทำแบบนี้

Q: What would you say is the most unique part of your creative process?

Planning, ideas, world settings, character settings, plot, story, scripts, gimmicks, game design, events, directions, sound design—and so on and so forth—all of which I create simultaneously as I work my way to the finish line. I suppose that is what makes me different from the others.

And every day, I continue brushing up the details until the last minute, when we submit the master. I think this is one of our unique ways of working on our projects, and it’s the strength of “A HIDEO KOJIMA GAME.”

Whether you’re creating a movie or creating a game, it involves having a massive team on a project, so the work is usually split up. Also, once the process starts, you can’t turn back, almost like a river flowing downstream. In my case, since I stop and check every day, it is possible to go back and correct things without wasting time. Even if a character has already been completely set up, designed, and modeled, I can easily modify and add in newly adjusted settings or designs and even change the role of the character in order to tweak some dialogue in a certain scene to make it more effective. This method may be similar to how Pixar operates, revising scene by scene until the very end.

เหตุผลที่ Kojima ทำแบบนั้นได้ ส่วนหนึ่งคงเป็นเพราะเขาเชี่ยวชาญศาสตร์ทุกสาขา หนังสือ หนัง ดนตรี ฯลฯ (ถ้าใครตามทวีต Kojima จะรู้ว่าแกดูหนังเยอะมาก) แรงผลักดันมาจากข้อจำกัดทางเทคนิคของเครื่องเกมยุคแรกๆ ทำให้ Kojima ต้องพยายามหาวิธีดิ้นรนเพื่อสร้างเกมให้ดีขึ้น ผ่านวิธีการเล่าเรื่องแบบวงการหนัง (กันดารคือสินทรัพย์ ของแท้)

Q: When did you first realize that the creative elements of filmmaking could be applied to video games?

First, I may need to clear up some misunderstandings. My creative process is not only influenced by films, but also by books, music, art, education, and every experience in my life that I have absorbed and digested.

I started creating games in 1986. At the time, game consoles had extremely limited capabilities. There were pixel and color limitations and also no music or voices, just beeps for sounds. Animation was also very simple. Characters had no faces, expressions, voices, personalities, or even backstories. However, even in this situation, screen layout and storytelling were possible to some extent. So, in a way, it was possible to use directional techniques that I had learned from movies and novels. This is because storytelling is a primitive human activity.

To be honest, back in 1986, I had no idea that games would evolve so rapidly, but I believed that games would one day be a comprehensive art form that would surpass movies.